Not Really Helpful

By Anthony Casperson

8-17-24

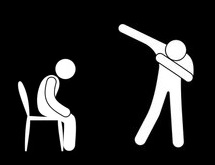

The camera centers on a person who’s just heard terrible news. Life has suddenly turned upside down for them. It’s never gonna be the same. And they’re in the midst of deep grief.

Into the frame enters another person who cares for the one grieving. This newcomer sits down and looks at their loved one whose in the throes of sadness, depression, and anxiety. Obviously, they want to help the person. They need to think of something. And then they have an idea.

It starts off quiet. Almost tentative. They start to sing a song to their friend. And not just any song. No, it’s an upbeat, happy song. While the grieving person pays no attention at first, they eventually look at the person trying to make them feel better. Maybe, there’s even a hint of a smile.

Then, by the midpoint of the song, the singer stands up and starts doing a ridiculous dance. And a tiny chuckle comes from the one with tears staining their cheeks. So, the other person begins to invite their loved one to join them. Stand up. Sing. Dance. Be happy and cheerful.

And finally, they do. It’s the climax of the scene. A reversal from quiet tears to singing silliness. Happiness in the midst of tragedy.

But how often does this happen in real life? How often can someone do something so tonally opposite to our emotions and then convince us to join them in that new mindset? Would we not, more than likely, view that person as emotionally insensitive? Consider their actions as something more hurtful than helpful? Do they really think that a little silliness can solve our grief? Acting like we just need a little perspective to change our “overreaction.”

More often than not, this “Just put a smile on your face” mentality ends up making the person feel worse. It can feel like the supposed “comforter” is belittling our emotions. Or not listening to what we’re saying, if we even have words to explain our depression.

I honestly can’t say that it’s only in movies that a happy song can help a grieving person. Given the right circumstances, with the right person, at the right point in the grief process, a little levity in the midst of the heaviness can be exactly what’s needed. But that window of opportunity is extremely narrow.

Far more likely, the attempt at comfort is not really all that helpful. And will receive a reaction that’s certainly not what the attempted comforter hoped for.

A few weeks ago, I was reading in the book of Proverbs and came across a word of wisdom that spoke to this very thing. “Whoever sings songs to a heavy heart is like one who takes off a garment on a cold day, and like vinegar on soda” (Proverbs 25:20, ESV).

It’s important, when dealing with the self-contained and pithy sayings from the book of Proverbs, for us to remember that they’re words which speak to the general way of things. They talk about common experiences among humanity, but aren’t always 100% applicable to each and every situation. There are exceptions. But that doesn’t diminish the truthfulness of the words for the vast majority of people and situations.

With that interpretive caveat out of the way, let’s look at the meaning of these words.

Solomon speaks to these moments where one person is in the midst of deep grief and another wishes to comfort them. But they do it in less than helpful manners. Apparently, there were people who said, “Just look at the bright side,” in ancient Israel too. Those who get in our personal space and force the edges of our mouths into a smile, thinking that would make us feel better.

But Solomon warns those who seek to comfort others that the desired reaction of happiness might not be the one they get. Instead, the attempt is likely to make things worse. Or get a highly reactive explosion that just leaves a mess which now has to be cleaned up too.

He likens this enforced happiness to someone yanking the clothes off of another on a cold day. It’s like he says, “I don’t know what you were expecting, but a shivering person who has their coat ripped off will only get colder. And you might’ve just started a fight.”

The second metaphor is like adding vinegar to baking soda. Yeah, a whole lot of activity will happen. It looks big and flashy. And might even look cool to outsiders—hence why we see it so often in movies. But in the end, you’ll just find yourself with a mess. It won’t help anybody. At least not the person who actually needed help.

Again, this is a statement of normal circumstances. If the cold person has just fallen through an iced-over lake and is now standing on the shore shivering, then getting them out of those soaked clothes is totally helpful. All the more so if you get them into something else dry, warm, and insulating. Or if you’re trying to teach a child about chemical reactions, then adding a little vinegar to some baking powder is an inexpensive and simple way to help.

But the point is that the comforter should keep in mind what the situation requires. What the grieving person needs at the moment.

The reason why so many of us see a grieving person and give them trite platitudes or happy songs is because we don’t know what else to do. And in an effort to not feel like we’re totally useless in the situation, we spew things that are unhelpful to the person in need.

But they’re very helpful to those of us trying to comfort another. We at least tried. We did something. We say, “It’s not my fault they’re too miserable to appreciate my attempt. Must be something wrong with them.”

In these situations, we’re unhelpful, at best. And harmful to others because of our selfishness, at worst.

So, some might be asking, “If singing happy songs to a depressed person isn’t the best way to comfort, what should we do?”

Well, let me tell you what’s probably the most direct application I have ever written or spoken. And this comes from someone who has been on both sides of deep grief.

What we need to do is ask, “What does this person I care for need the most right now? Ear, shoulder, or hand?”

I’m sure that looks like an odd question to ask. But the point is to ask whether they need: 1.) An ear to listen to them, 2.) A shoulder to cry on, or 3.) A hand to do something practical.

Often what a heavy heart needs is someone to listen to them. It’s not the time for the comforter to speak very much at all. Not time to give them platitudes. Not time to give a theological discourse on suffering in the life of a follower of Jesus. Not even time to make tiny corrections to what the depressed person says—no matter how wrong or dissonant the words they say are in relation to reality.

See, the words that a grieving person says are often a way for them to grasp for sense in a senseless situation. At any other time, when reasonable faculties are in play, the person would never say or think the things they do while in the midst of grief. But the problem is that they literally don’t have the vocabulary they need to process the pain they’re experiencing at that moment.

And the only words that come to mind are ones that are full of logical inconsistencies and wobbly half-truths. It’s why someone can say that nobody loves them, when the person listening to them is living proof of the opposite. They’re expressing pain at feeling unloved by a particular person. Or group of people.

Another example of a person speaking strange words that don’t really make sense actually comes from the sermon I just wrote this week. (It’ll be uploaded at the end of September, if my calculations are correct.)

In 2 Samuel 1:19-27, David expresses his grief over the death of Jonathan, his best friend in the world—and the death of Saul too. And in verse 21, he literally curses the mountain they died on. Mt. Gilboa’s catching strays here. He’s not literally hoping that the mountain never sees rain or dew again. He’s expressing the aridness of his own heart that will never be refreshed by his closest friend again.

The point for we who seek to comfort others is that some people just need an ear to listen in a non-judgmental manner while they express the pain and sorrow. The exact definitions of what they say might not make sense. But to their grieving heart, they’re the words that best express the mixed jumble of emotions flowing through them.

Secondly, a heavy heart might need a shoulder. Again, not time for the comforter to talk a bunch.

The shoulder is there to be strength for failing legs. And an altar for their sacrifice of tears. It’s for when a person doesn’t even have coherence enough in their suffering to find words. When groans are all that their grief can form.

We have to be cautious because of personal space here, but even sitting beside the person in silence is enough to remind them that they’re not alone in their grief. Presence can speak volumes more than any words can. A squeezed shoulder shows more than a million happy songs ever could. A shared tear becomes a flood of comfort.

While no one would call the three friends of Job good comforters, most would agree that their wisest moment of comfort came in Job 2:13. “And they sat with him on the ground seven days and seven nights, and no one spoke a word to him, for they saw that his suffering was very great.” It was only when they opened their mouths that the trouble began. And their comfort failed.

Comfort is often best when shown, not told. Words can lie, but our presence lives the truth of love and care. And a grieving person doesn’t need more lies. They have enough lies in their own heads, trying to keep them in their sorrow. Don’t add to it.

The third possibility for comfort to a heavy heart is a helping hand.

It’s placed third for a reason. Because it’s an easy escape from our discomfort while listening to someone flail in their sorrow, or while sitting in the silence as they ugly cry and leave snot all over our clothes. They can sit alone in their grief while we cook a meal for them—usually in our own home, far away from them. They can lay in bed crying while we drown them out with the sound of a vacuum cleaner. They can stay inside while we fix the hole in their roof because the rainclouds found a way reach them in their sorrow.

Helping grieving people in practical ways is often our go-to out of the three options. It’s easier. But the thing is that there can be a disconnect between the reason for the heavy heart and the helping hand. Sure, there are some things that fall to the wayside while in depressive moods. Like cooking meals and doing errands. But practical actions that are outside of the sorrow have limitations in their helpfulness. I mean, eventually a mountain of casseroles are gonna spoil.

Better yet is the practical action that aligns with what makes the heart heavy. Like, if the grieving person also has to make funeral arrangements, then sitting down with them to make a list of all of the preparations that need to be made could be helpful. Spreadsheets can be comforting. Who’d’ve thought?

I’m only giving one very specific illustration here because the practical steps will be specific to the reason for the sorrow and the relationship the comforter has with the person. But don’t just run to the old faithful options just because you can’t think of anything else.

For the most part—whether what is needed is an ear, a shoulder, or a hand—what a heavy heart really needs is someone to be there for them. To reinforce the fact that they’re not alone. Someone who doesn’t judge their mess at this worst moment in their lives. Someone who isn’t there with some trite old saying or enforced smiles. Someone who is willing to be there in the discomfort of sorrow.

The need is for a comforter who is there for them. I repeat, for them. Not for sorrow in the abstract. Not out of necessity to make ourselves feel good because we tried something. Not with lies and fake happiness. But real and personalized care for them.

The answers might vary greatly, but when it comes to showing comfort that actually helps, we must ask the same question. “What does this person I care for need the most right now? Ear, shoulder, or hand?”